4 Naming components and Concepts

Taeke de Jong; Jürgen Rosemann

4.1 Components and concepts in drawings......................................... 1

4.2 Focus: Seed of components and

concepts.................................... 2

4.3 Unravelling scale............................................................................. 4

4.4 Context: ground of components and

concepts............................... 6

4.5 Unravelling overlaps........................................................................ 7

4.6 Naming transformations: instruments

of concept formation........... 8

4.7 Conditional positioning of concepts............................................... 10

4.8 Conclusion..................................................................................... 12

Specific terminology exists in each scientific discipline enabling effective

description and specialist communication. In some disciplines the number of

defined concepts is

relatively small (as in logic, mathematics, physics, history and geography,

even though with the last two the number of names is uniquely large), in others (chemical nomenclature, medical

science and above all in biology and ecology) this is very large. This has

partly to do with variation in the phenomenon to be explained.

What can be done when a designing

discipline, such as architecture, is expected to create these phenomena

and to increase their variation (especially in form and structure)?

A few technical architectural dictionaries exist[1]

(concepts) and encyclopaedia (concepts and

names); however there is little interest for them in architectural design; they

are mainly of historical interest. This by no means covers the topicality of

new design assignments. In architecture there is an infinite number of

proposals created; partly expressed by drawings and pictures. It is thought

that from each drawing new concepts and conceptions may be derived allowing

parts of the design process to be subject of discussion. However, their number

is so large, that this vocabulary will never become widely accepted.

A research project into reference

words, which summarise the competence of professors in architecture[2], brought to light that many subjects and dilemmas of study

by design, design, design research and typology could hardly be reproduced in

everyday language or technical language. The number of new terms (neologisms) in this profession is, therefore,

large.

Designers show a distinctive

creativeness in using neologisms for the explanation of their designs,

neologism like that empirical researchers simply dismiss as of no use in their

jargon (family structure, age, income). However, it is of utmost importance that

these concepts are taken seriously because they show the inadequacy of

empirical jargon. They can herald a change in focus demanding another concept definition. Intensive defining is,

therefore, not always the right thing to do. Conditional positioning is an

alternative for precise defining.

The sheer size of the Index of this book (see page ) is an indication of the prime importance

of naming in the science of design. The first naming of components, concepts and design activities in the transformation of the earth’s surface is determining the focus from where the remainder is named and considered. That this focus

may be chosen differently, implies that a number of vocabularies are possible and desirable. Naming, typing and making legends are hiding an implicit, often blockading classification within which both study and design will express themselves subsequently and necessary. Already a seemingly

objective description comprises in its terms at least one tacit pre-supposition that one should be conscious on in order to be able to speak in a different

language about the same phenomenon.

The importance of naming and

therefore implicit classification for design comes nowhere so directly to the

fore as in the Chapter of the section technical study ‘Classification and

Combination’ (see page ). In it, the discussion, of a standing measured by

decades, about naming the building materials and components is described as

well as the shortcomings of any classification for a design opting for a

different selection of building blocks in order to get to new designs. Any designer is facing, in each compositional task, such tacit, sometimes stimulating,

but usually blockading pre-suppositions with which components have been named or imagined traditionally.

This Chapter gives some indications

how the components of an image and their re-construction into a concept may be delimited and named. This way it is becoming possible to talk about them and to retrieve them.

4.1 Components and concepts in drawings

A picture says more a thousand

words, but which words are these? This question is of importance for the

scientific status of drawing, its documentation and retrievability.

A drawing is made in order to read

something from it. Legibility is dependent upon explicitness and expressiveness.

That is not the same. An explicit drawing, like a black circle on a grey field

with for legend units ‘black = built’ and ‘grey = vacant’, for instance, may be

very explicit, but is not expressive.

|

|

|

Figure 1 Information content of a drawing |

The upper plot divisions are more

expressive, while their legends (vocabulary) are more comprehensive and have been spread in more

than one legend plane in the drawing (information content). When the borders

between the legend units are drawn vaguely, the drawing may be more expressive,

but it is less explicit. The precise positioning of legends planes has more tolerance (see paragraphs and ).

Less explicit drawings make sense for creating an impression, but say less in a

scholarly than in a poetical sense. Nevertheless they are essential in the

designing process.

While consulting an archive of

drawings it is only important to retrieve the drawing from which may be read

what one wants to know. So it is not only important from a scholarly viewpoint

to know what a drawing is depicting, but especially which properties,

attributes and operations may be read from what is depicted.

4.2 Focus: Seed of components and concepts

The chosen focus primarily determines the viewpoint from which components and

concepts are defined.

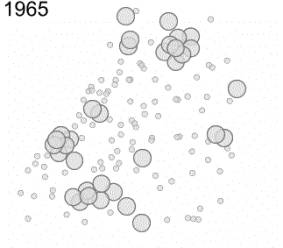

During the design process, the interpretation of the location determines in a major way the first components with which the

composition of the design is created. This way, over the years the

interpretation of the urban area in the Randstad has changed focus. During the process the selection of the

constituting and surrounding components of the image and the concepts related thereto did change. In the figure below the Randstad is

represented in units of 100 000 and 10 000 people (large and small

circles) in 1965 and 1995 respectively.

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 2 Succession of sprawl |

The large circles have a radius of

3km and represent reasonably well the urban surface area, which on average in

the Netherlands is occupied by 100 000 inhabitants. This also applies to

the small circles of 10 000 inhabitants. Where the circles overlap a

higher than average population density for the Netherlands exists. The

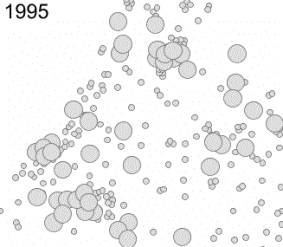

interpretation of this urban area throughout the years is similar to the

formation of a different structure of the stars into a different constellation.

Through this a different political,

design technical and scholarly grasp on the composition also originates.

In 1965 the Randstad was made up of

a few large and a few small towns, recognisably separated by buffer zones and a ‘Green Heart’ between them. In 1995 it was mostly called a ‘north-wing ‘ and a

‘south-wing’. The Green Heart is becoming thought of less as a component. The

‘focus’ is shifting. Now it is generally called a ‘Deltametropolis’.

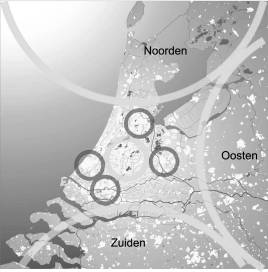

A different focus is created upon

the surrounding landscape based on the concept of a Deltametropolis, than one

based on the concept of a north- and south-wing of the Randstad with Green

Heart. The placing of the first components in the composition of the

Netherlands determines the concept formation for the rest. In the figure below these concept shifts are

represented using larger units (agglomerations, regions, parts of the country).

|

|

|

Figure 3 Big cities around the Green Heart |

|

|

|

Figure 4 North and South wing |

|

|

|

Figure 5 Deltametropolis |

Historical sciences show more

examples of limited object constancy. Languages, people, nations and

social categories appear, thrive, diminish, disappear or shift on the map in

relation to their territory. The ability to free oneself from old categories,

to choose a new focus, is the hallmark of creative researchers and designers

(see also page ).

4.3 Unravelling scale

Changes

in abstraction within a reasoning can lead to paradoxes like the statement “I am

lying”. If I am lying, I speak the truth and vice versa. It is a statement and

at the same time a statement about

the statement itself. Such self-reflexive statements were banished from the set theory at the beginning of the last

century by Russell[3]. He would not allow changes in abstraction using a mathematical

argument: “A set of sets may not contain itself”.

This wisdom has by no means entered into everyday language, not even in

science.

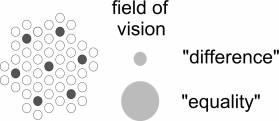

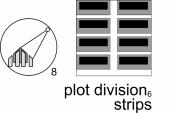

The accompanying figure shows a

spatial example of concept confusion, based upon a difference in the scale of

consideration (scale paradox). It is shown here that identical

spatial patterns allow different conclusions to be drawn when elements are

involved in the consideration using a differing scope (scale level, largest frame, smallest texture grain).

|

|

|

Figure 6 Scale paradox |

For example if in the figure above

one takes one circle each time and the surroundings into consideration then one

must ascertain a difference, although equality should be ascertained when one

repeatedly compares groups of seven with the surroundings. Something similar

applies to the consideration from inside to outside and from outside to inside.

The paradoxical concept ‘homogenous mixture’ indicates precisely which dilemma

this entails: it is homogenous at a specific scale level, at a lower

abstraction level it is heterogeneous.

The concept ‘clustered diffusion’, well known in Dutch urban

planning, is another example. For concepts like that the question must be asked

immediately: ‘using which scale for one, and which scale for the other?’.

Moreover, this figure shows that such confusion of tongues is possible using a

factor three linear scale level difference. Between the grains of sand and the

earth lie 7 decimals; therefore there are more than 14 concept confusions

lurking.

This gave

rise to allocation of a frame and a grain which differ systematically to other

scale levels by a factor of around three for architectural categories, (discourses, drawings, uniformity in

legends, concepts and objects) in the urban development[4] and the technology of building[5]

in order to enable the context of the category in question to

be defined (such as on other scale level).

FRAME |

NOMINAL RADIUS |

|

|

Global |

10000 |

|

|

Continental |

3000 |

|

|

Sub-continental |

1000 |

|

|

Nationa |

300 |

|

|

Sub-national |

100 |

|

|

Regional |

30 |

|

|

Sub-regional |

10 |

|

|

Local | Town | Borough |

3 |

|

|

District | Village |

1 |

km |

|

Neighbourhood | Hamlet |

300 |

|

|

Ensemble | |

100 |

|

|

Building complex |

30 |

|

|

Building |

10 |

|

|

Building segment |

3 |

|

|

Building part |

1 |

m |

|

Building component |

300 |

|

|

Superelement |

100 |

|

|

Element |

30 |

|

|

Subelement |

10 |

|

|

Supermaterial |

3 |

|

|

Material |

1 |

|

|

Submaterial |

<1 |

mm |

|

Table 1 Scale articulation |

||

The frame stated is labelled with a

measurement, e.g. ’10 m radius’. Such a ‘nominal measurement’ may be

interpreted as ‘flexible’ up to the measurement of the adjacent radius, e.g.

‘3m up to 30m radius’.

|

|

|

Figure 7 Scope of nominal measures |

4.4 Context: ground of components and concepts

|

|

|

Figure 8 Object and context |

As soon

as one has ‘placed’ an architectural proposal, object, concept, conception,

research or design on a scale level or ‘radius’, the rest is ‘context’. The concept has obtained an

‘interior’ (everything which is smaller than the texture grain of the object) and

an ‘exterior’ (everything which is greater than the frame of the object). This

does not just mean in the widest sense of ‘spatial context’, but, also, more

specifically, an ‘ecological’, ‘technical’, ‘economical’, ‘cultural’, or

‘managerial’ context. These contexts are also scale sensitive.

When naming the scale boundaries a

concept is, from a particular viewpoint, spatially ‘placed’, regardless of the

way a similar problem exists in the time. The concept ‘Perspective’ in time exists here as an analogy

for ‘context’ in space, which becomes significant when the intended and

unintended effects of a design are to be interpreted, named and estimated. In

which perspective does this happen, with which plan

horizon and under which assumptions with regard to external developments

(initiating or controling government, an opportunity- or tradition directed

culture, growing or stagnating economy, technology which is successful using

function combinations or on the contrary using function separation, an

increasing or decreasing spatial pressure).

|

|

|

Figure 9 Different dynamics and perspectives |

Articulation of scale can clarify the

concept ‘goal’ and ‘mean’ on the level of policy: if the

State wants to reach a goal through a subsidy, this mean may be a goal for more

local authorities. In this way economies are sub-divided in micro, meso and

macro economies. Concepts like ‘loss’, ‘profit’, ‘savings’ and conclusions

about them may not be inter-changed between them, even if the used words sound

the same. Something similar is valid in time: if a goal has been reached, the

result has become a mean for a goal further away. It needs no mentioning that

the meaning of a concept depends on the context and the perspective within it

is used and that it is often used ‘removed from its context’[6].

The building process always takes

place in a social and material context and in a perspective based thereon. Each

stage can have a different political, cultural, economical, technical,

ecological and spatial context and employ, by the same token a language game[7]. The resulting conceptual confusion can often be solved by asking on

which scale level the ambiguous concepts have been intended.

|

radius frame stage |

|

|

|

|

|

m |

|

|

|

mm |

|

300 |

100 |

30 |

10 |

3 |

1 |

300 |

100 |

30 |

10 |

|

|

initiative |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

programme |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

development |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

design |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

effect analysis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

execution |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

usage |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

maintenance |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

evaluation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

demolition |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 2 The context during the building process |

||||||||||

4.5 Unravelling overlaps

Once the perspective and context of

the architectural system of concepts have been determined, one must check as to

how far the concepts overlap. Overlapping concepts are lucrative in the acquisition of research, because one is

allocated a budget in order to research the same thing using another name and

possibly with slightly different limitations. However, they actually hinder

retrievability and accumulation of research results and therefore growth of

knowledge and proficiency. With this in mind one must not disallow new concepts

(and then for example create a ‘thesaurus’ using permitted and well-defined

concepts.) After all, the value of university research is in extending

boundaries, shifting perspectives and changing focus.

The domain of overlapping concepts

can be divided by giving the overlap a new name of its own.

Supposing that, in a building one

makes a distinction between load bearing, dividing and finishing structures to

determine their effect on the required design-effort, their effect on manpower

by production or to divide the budget between three participating parties. Then

overlapping can lead to disagreement.

|

|

|

Figure 10 Overlapping concepts |

Set theory offers in this case

symbols for ‘without’ (asymmetric difference, represented using \) and the ‘overlapping between’ (diametre, represented using

∩). This results in 5 exclusive concepts: (1) supporters\partitions (2)

supporters∩partitons (4) partitions∩finish, (5) finish\partitions

and (3) partitions\(supportersUfinish), whereby U stands for ‘union’ (in this case from two disjunctive sets which are not considered to be overlapping). One can here also use

concepts like (1) ‘non-partitioning supporters’, (2) ‘partitioning supporters’

etc.

Things become more complex, when a

designer creates (6) a bearing construction as a finish. The Venn-diagram then

indicates three overlapping circles with the categories ‘bearing and finishing’

and ‘bearing and dividing and finishing’ If this was unforeseen during the

budget apportionment, to which budget must the time spent on the design be

charged? Who makes the profit during execution? Therefore, in practice, an

incorrect concept formation leads to confusion, let alone in science. This is

very much the case when one wishes to compare different situations whereby the

overlapping areas are not specified. It is also plausible in this case that an

implicitly overlapping system of concepts is an obstacle for combined

architecture innovations.

Neologisms may be required on the

road to unambiguity, if one locates their domain in such a manner with respect

to other concepts, (for example using Venn-diagrams) in order to accomplish a

system of concepts. The requirement to avoid overlapping areas applies again to

the other concept location.

|

|

|

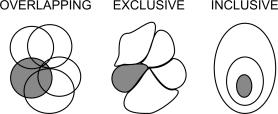

Figure 11 Exclusive and inclusive concepts |

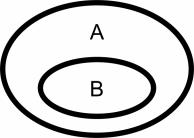

The procedure is: to divide the

domain of overlapping concepts once again into exclusive

concepts and, if required, summarise them in order to accomplish a system

of inclusive concepts giving insight into abstraction

levels. The question “can one imagine ‘B’

without ‘A’ “, combined with the reverse question can aid this and yields

surprising results especially with an inclusive system of concepts[8].

If the answer to both questions is negative

and/or affirmative then these are respectively overlapping and/or exclusive

concepts and if the answer is different, these are inclusive concepts with an

asymmetric relation.

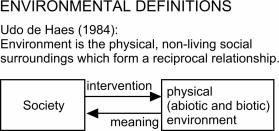

An irritating concept confusion

exists when one places non-equivalent categories of different abstraction level

against each other such as ‘man and society’ or ‘man and the environment’ and

then also includes this in a schedule, which conceals more than it

clarifies. A good example of this is Udo de Haes’[9] environmental definition, however, almost every scientist was an

accessory to this.

|

|

|

Figure 12 Environment according to Udo de Haes |

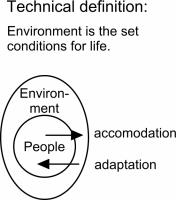

However the technical environmental professors (Duijvestein, De Jong and Schmidt) present a ‘technical definition’[10].

|

|

|

Figure 13 Environment in technical sense |

After all, one cannot imagine a

society without an environment, but one can imagine an environment without

people. The first schedule is, therefore, misleading from a technical point of

view. Maybe this definition difference is typical for a contrast in language

games between empiricists and designers, the way in which they reduce reality.

The example puts the problems of the relations between concepts up for discussion. The second representation

implies an actual asymmetry in the relationship between man and the

environment, lacking in the first representation.

Does defining consist of making connections with other concepts? Are concepts

therefore nothing more than a summary of potential connections (valencies) with

the rest, their context? Is a property something different from a relation, an action that shows the feature?

What name should we give to such actions? Does the naming of actions form

another sort of concept than the naming of objects? It is quite similar to the

physics argument: whether light is a wave- (action-) phenomenon versus is light

a particle- (object-) phenomenon.

4.6 Naming transformations: instruments of concept formation

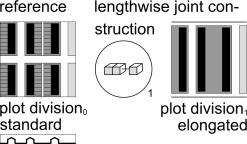

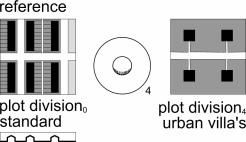

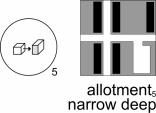

The figure below shows a reference

plot division0 with 48 houses on one hectare with an operation O1..3

transformed into another plot division1..3 with the same number of

houses per hectare (ceteris paribus[11]).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 14 Three transformations on one

reference |

|

All representations (images, nouns,

adjectives and verbs) in this figure are concepts, abstract representations. They

represent a collection of examples in reality (extension of the concept) and do not form the image of one specific

situation. The square images are plot divisions: possible layout distribution of

built-on space and a few categories of open spaces with mutual bearing. The

open space is split into public landscaped areas and private grounds (light and

dark grey) and public road space (white). They maintain a bearing upon each other within

the plot divisions in the sense that if the built-on area (independently)

varies, then the open space will also (dependently) vary. It can also be said

that: open space y is influenced by, or an action of, built-on space x: y(x) open space(built-on space). The expression y(x) is called a sentence function. As soon as this connection is operational then the concept has become a function: y=f(x), composed of operations between variables (see paragraph ). A Mathematical operationalisation would be: open space = total space – built on space. However,

there are innumerable qualitative design-operationalisations (transformations) possible within this quantitive

rule.

From the diagram with the plot

division transformations the operation of lengthwise joint construction, can be

read on a reference: long blocks(plot division). Such a notation

object(subject) where the brackets mean ‘as operation of’, is also a

full-sentence function that has become independent[12]. The operation is dependent on the way in which one builds adjacently:

in the length, the width or the height of the building block. The function can

be used as key-word for the drawings specified by transformations.

The noun ‘plot division’ and its depiction are comprising here this way the

constituent legend units[13] (constituent concepts) and (spatial) connections between the legend

units. In the word ‘plot description’ this stays implicit, in the picture it is

explicit. Focus can change by alternative grouping if ‘private space’ is a

legend unit composed of built-up area and gardens. The meaning of

‘plot-division’ changes accordingly, perhaps better named by ‘parcelling’.

The verb (evoked in the circles) pre-supposes an imaginary connection

within time between the plot divisions mutually: first, the reference, then the

operation and then the result. If one is opting for a different reference (for

instance neighbourhoods rather than houses), the same operations would have a

different result. This connection can more generally be described as ‘plot

division’ as operation of a reference: plot division(reference)[14].

The adjectives give one property of the plot division, or actually of the built part of it (pars

pro toto[15]). However the concept ‘plot division’ is a set of properties; most of them

lack verbal equivalents. A property can be described as an operation. Zoning is

an operation of the plot division: resulting in a property zoned(plot

division(reference)). If a property serves the identifying of a depiction, this

property is termed an attribute.

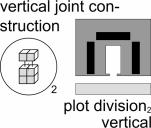

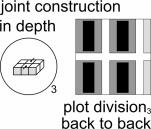

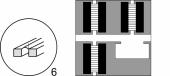

In the figure below operations are

visualised using the same reference plot division, however these can not be

reproduced using just an existing verb. However, naming the transformation by a

sentence function result (origin) could be efficient for retrieval.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 15 Transformation difficult to name |

|

Design operation4 could

be called ‘compact building’ or ‘concentration’ in three dimensions (length, height,

and depth) on a scale level of one quarter of a hectare. This results in urban

villas measuring 15x15x15m. On a

scale level of the hectare as a whole, however, the concentration (ceteris

paribus) would accommodate one building measuring 24x24x24m. So, the term

‘concentration’ is a scale sensitive transformation

Operation5 is a form of

concentration in length. The result being a narrow and deep dwelling when using

an equally sized plot division surface (ceteris paribus). This has a

number of effects upon the open space and its technical facilities.

Operation8 results in

southerly directed strip plot divisions, therefore, enabling all of the houses

to be orientated towards the sun and, therefore, can also be internally zoned

for warm and cold rooms. This operation is difficult to describe using a verb;

this is why it is visualised with the aim of this operation (zoning), which

requires a reference point outside the plot division (the sun, the south).

The adaptations of the plot

divisions are mainly geared towards the built-on space, but at the same time

they also have a spatial effect, which is difficult to define, on the public

landscaped areas, paving and the open private space. The result is known as an

effect on the built-on space, but the result of the adaptation is much broader.

In architectonic and urban

development, designing always contains an intervention in an existing situation, focusing on specific effects. When one

is in the position to name these interventions as design operations

(transformations), then one can summarise many patterns as result of a few

transformations on every reference.

The concept ‘concentration’ is an

example, if one specifies this concept per scale level and direction.

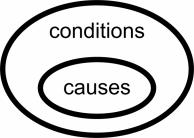

4.7 Conditional positioning of concepts

What is called ‘assumption’ in our

imaginative capacity is a ‘pre-condition’ in reality. If I'm driving a car, I

assume that there is petrol in the tank. This is also a pre-condition to

actually being able to drive. If something does not ‘work’, then one of the

conditions for its working is lacking, in this example the petrol. Such a

pre-condition is a ‘cause of failure’, the ‘cause’ of a non-event that one had

indeed expected (assumed). Yet the classical notion of ‘cause’ does involve an

‘occurring event’, even though one does not expect it (for example the cause of

a fire). With the concept of ‘cause’, then, one is actively thinking about an

event that has come before and that caused perceived consequences (active

cause).

All these causes are a condition for

something to happen, but not all conditions are also causes.

|

|

|

Figure 16 Not every condition is a cause, but every cause is a condition for something to happen |

There are many more conditions than

there are causes. Petrol, for example, is not the only pre-condition necessary

to be able to drive a car. There also have to be pipes that supply the petrol to

the engine, there must be an engine, and this engine must be able to transfer

its capacity to the wheels. And indeed, the car must have these wheels. The

design of the car is actually the collection of pre-conditions needed for one

to be able to talk about a car. These are object pre-conditions, but there are

also a basically infinite number of context pre-conditions. I cannot drive a

car if I am sick, if there are no cars or ways for me to drive, or if someone

prevents me from doing so for whatever reason. Thus the context is a collection

of pre-conditions for the architectural object.

Studying the context and object

pre-conditions does not result exclusively from the linear logic of causal

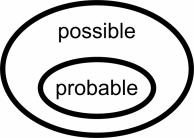

thinking. Under certain conditions, something can happen, or in the case of a certain cause it will probably happen. Conditional

logical does not always unlock the probable, but it does unlock the possible.

|

|

|

Figure 17 Any probable event is per definition possible, but there are improbable possibilities |

This logic fits in with study by design.

Just as there are chains of cause and effect, there are also pre-conditional

chains by which, under certain circumstances, patterns and processes are not so

much predictable, but rather imaginable. This imaginability is introspectively

verifiable using the test, "if I can imagine A without B, but not B

without A, then A is the pre-condition for B".[16] We call it ‘conditional analysis’.

|

|

|

Figure 18 'A not imaginable without B' |

Petrol is the pre-condition for a working petrol engine, but a petrol engine is not a

pre-condition for petrol. This is not a case of causality since petrol is not

the cause of the working but only one of its conditions. A load-bearing structure is the

pre-condition for a roof, but a roof is not a pre-condition fort a load-bearing

structure. Thus one can pre-conditionally position design elements in regard to

one another. Aspects of the context can be studied as pre-conditions for parts of the design. Design

study and study by design considers variation in

pre-conditions. Within the design process, results from certain design phases

are pre-conditions for a continuing of the design.

Mutual conditional

positioning of concepts shows the very possibility of definition itself. One can not define a concept in terms that pre-suppose the

concept itsef. Whether the concept to define is contained in the defining terms

or not is brought into light by conditional analysis.

The conditional analysis goes:

1 'Could you imagine terms A without

B?

2 'Yes'

3 'Could you imagine B without terms

A?

4 'No'

5 'Then terms A are pre-supposed by

B

B could be defined using terms A.'

|

|

|

Figure 19 Terms A pre-supposed in a definition of B |

Conditional analysis can help

positioning terms for defining abstract and vague concepts. A useful example is

given in 'From possibility to norm'. In

the next sections of this book crucial concepts in describing design processes

could be positioned like this:

|

|

|

Figure 20 Stairs of imagination |

However in this figure the focus is on imagination of not yet exising objects produced in a design

process. It is a designers' focus defining a model in terms of design. An empirical scientist perhaps pre-supposes a

reality without which s(he) can not imagine models. S(he) will position the

terms the reverse and define a design in terms of a model. To understand differences in focus one should

enter a higher level of philosophical abstraction of discussing such

differences on itself. In Chapter (see

page ) we will discuss them in the perspecive of idealism and materialism.

4.8 Conclusion

In this Chapter we tried to discuss

naming concepts and components in a conditional way. It started with focus as

pre-condition of choosing components, frame and grain, getting grip on context, unravelling overlaps, naming

transformations and conditionality in technical design and in defining concepts. So the sequence

supposes conditionality on a higher level of abstraction than the subjects

discussed, the level of the discussion itself. Should we start on that level of

discussing discussions with conditionality and end with focus? That kind of

focus perhaps goes beyond imagination. Anyway, the Bible starts with naming..